Mechatronics

The word mechatronics was coined a year after I was born. I've been interested in the topic for most of my life, but I don't remember hearing that word until earlier this year. Mechatronics describes the intersection of mechanical systems, electronics, and software. When I was a kid, I thought of mechatronics as robotics. The current definitions make mechatronics the broader field and indicate that robotics includes some sort of autonomy and the manipulation of objects. That difference is lost on me.

My earliest robot memories are watching reruns of Lost in Space and Johnny Sokko and his Flying Robot. The Lost in Space robot, named Robot, is famous for its warning, "Danger! Danger Will Robinson!" I wondered, even at that early age, what sort of sensor detected danger. As an adult, it's obvious that it's a neural network that examines available data and makes a danger determination. It's not like there's a rare element whose electrical conductivity changes in the presence of danger — that would be cool though.

|

|

The robot from Johnny Sokko and his Flying Robot, named Giant Robo [sic], had rocket engines on its feet that allowed it to — as the title suggests — fly. I built a wooden (not to scale) version of Giant Robo from scrap lumber. I asked my dad for a match to light it on fire. He asked why I wanted to do that. I explained that the rockets on the robot's feet needed to have flames so that it could fly. That moment may have been formative: teaching me that making things work in real life is harder than one might initially think. That bit of wisdom might have sparked my desire to be an engineer.

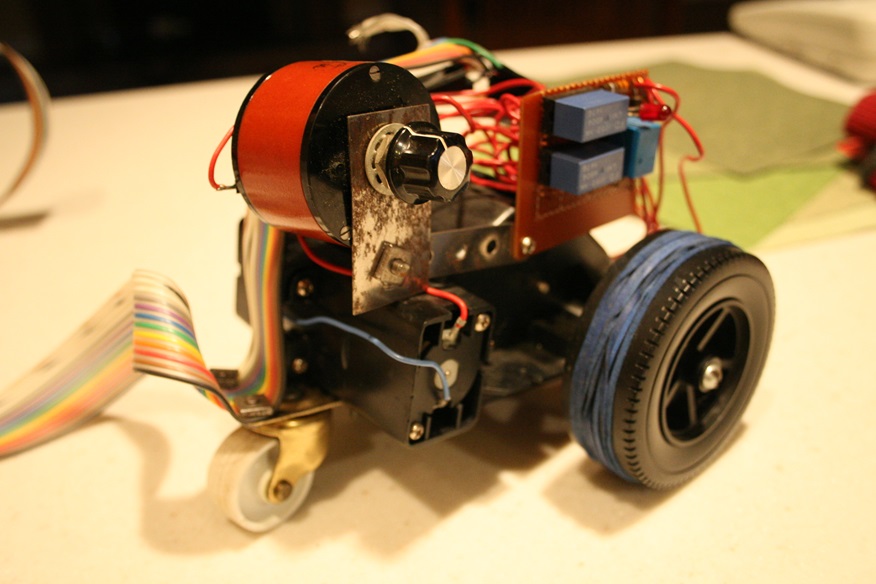

I have fond memories of working on electronics projects in high school. During my senior year, a friend and I built what I believe was my first robot as our science fair project. Pictured below, its name was Small Mobile Intelligent Robotic Platform or SMIRP. It was designed to be a maze-following robot. It could follow aluminum foil using infrared sensors, but we never got it to solve mazes. Robots and forced acronyms are strong indicators of a future engineer.

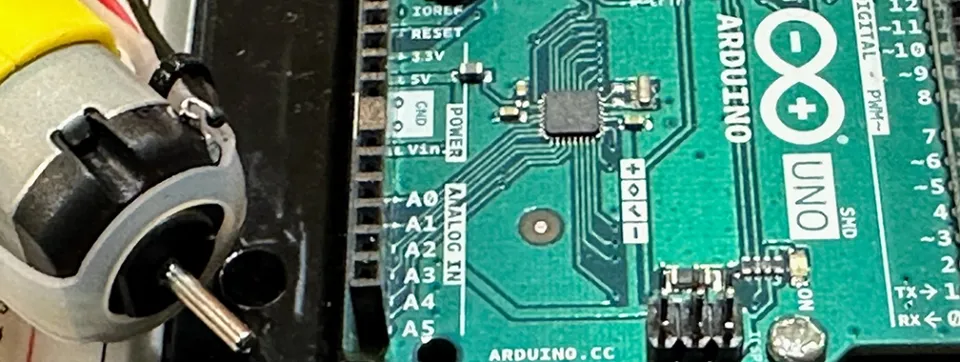

Robots are on my mind because I volunteered to assist the Physical Computing class offered by the makerspace at Trent's high school. Physical Computing is mechatronics or maybe robotics depending on whom you ask. There were three students in the class, so we got to really focus on some engineering. We spent the first few weeks exploring the Arduino computing platform. The SMIRP had to be tethered to the joystick port of my Atari 800 to provide software control. In the twenty-first century, you can get useful Arduino computers that are about the size of a stick of gum and run off AA batteries. We got to experiment with LEDs, ultrasonic distance sensors, servos, and motors. High school Rhett would have been really excited.

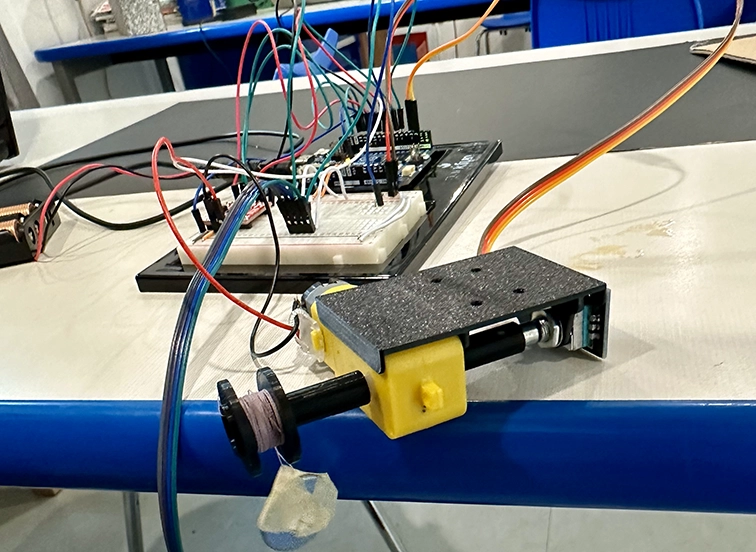

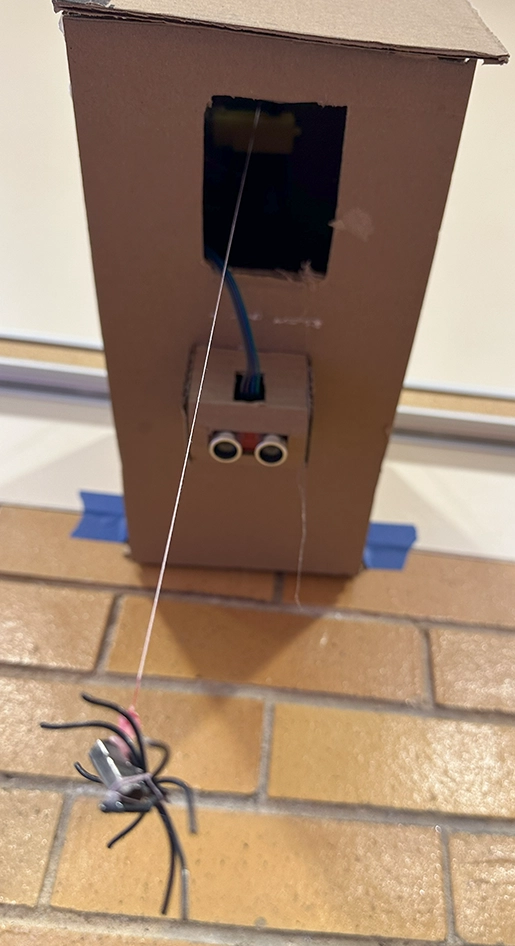

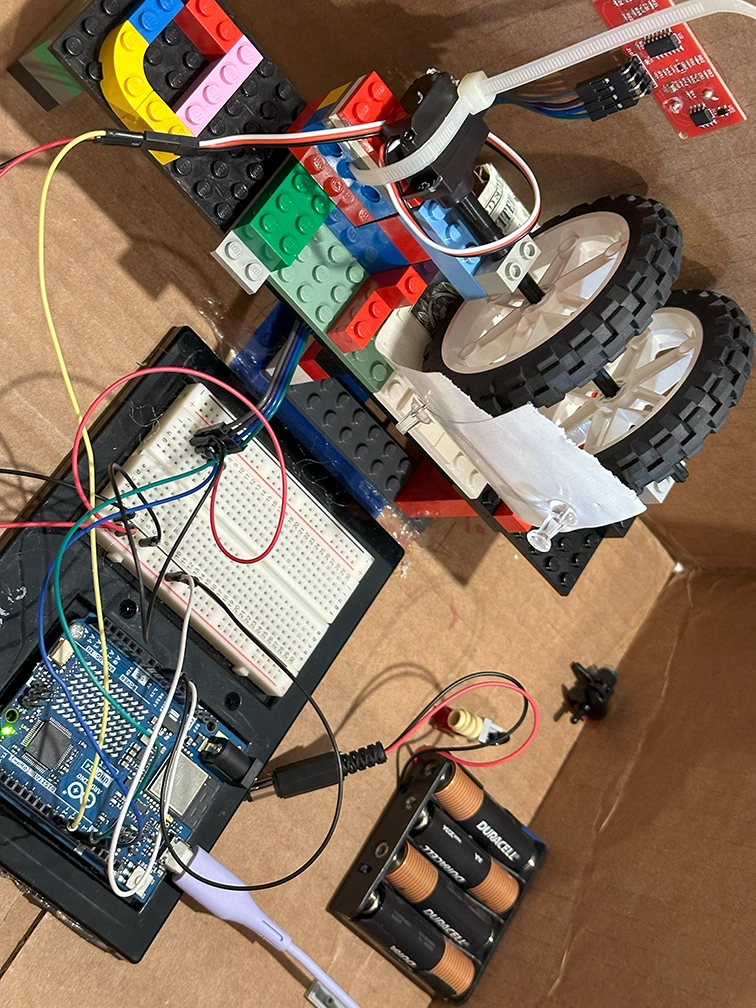

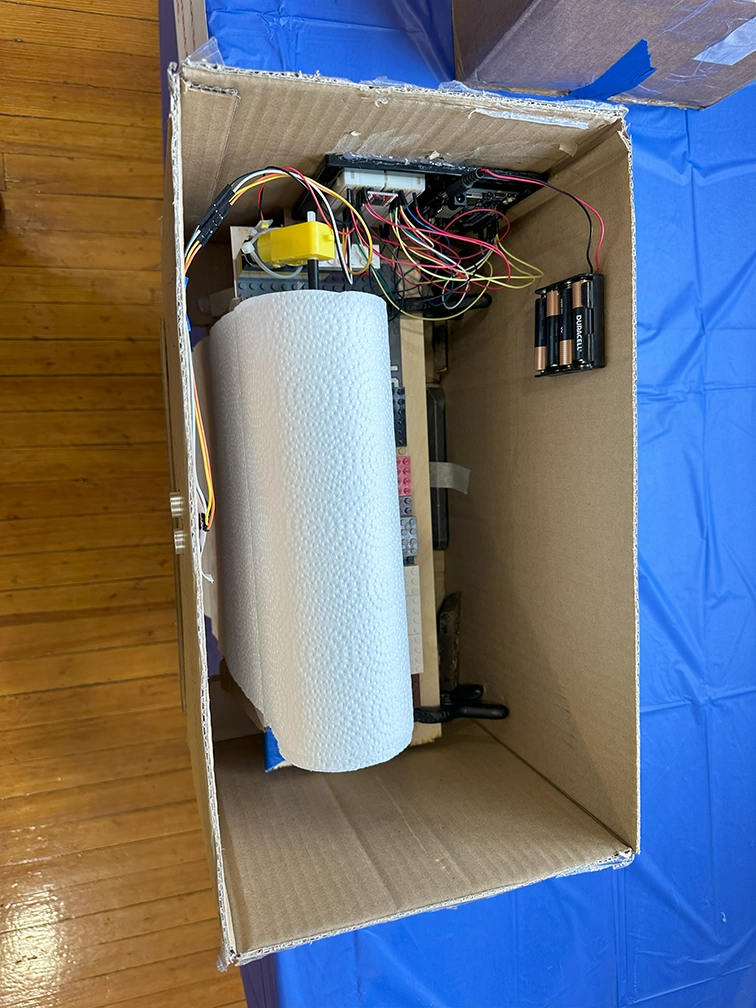

After doing some foundational work, the students picked an individual project to work on. Last week, those projects got shown off at the school's Expo. The Expo gives parents the opportunity to come in and see all sorts of student projects. There's drawings, photography displays, cabinetry, and musical performances. This year there was also Physical Computing. All three projects worked pretty well. One project pushed a dollar bill out a slot and then retracted it when someone approached. Another student built a motion-activated paper towel dispenser. The third lowered a spider down from a door when it detected something below. Here are the internals of the spider drop project.

First, we tried lowering and raising the spider with just the motor and the Arduino's internal timer. The motor is the yellow part in the picture above. It has a spool of thread with a washer tied to it as a prototype spider. The motor spins to lower the spider in response to the motion sensor being triggered. For the machine to operate more than once, we needed to be able to lower the spider and raise it back up to the height it started at.

We learned that the motor didn't move at a reliable speed. Lowering the spider for five seconds and then raising it for five seconds did not return it to its starting height. Further experimentation showed that raising the spider consistently took longer than lowering it, and the timings varied with each attempt. We needed to be able to accurately know how many times the spool had rotated to get the height correct. So, we added a rotary encoder on the other side of the motor to count the rotations of the spool of thread. The encoder has bits of copper that rotate past one another. While the encoder spins, those bits of copper act like a switch that the computer can see turning on and off. Ideally, you would see the signal go on and off once each time the copper contacts rotated past each other. In reality, a single click of the encoder might generate a several on and off events in quick succession. So, we had to find a software strategy for cleaning up that mess and counting correctly. It's hard to make things work the way you want.

Ultimately, Physical Computing class was a success. The students were engaged and interested in getting their projects to work. They learned that getting things to work is hard, but the difficulty did not discourage them. I had a good time, even though no one lit anything on fire in an attempt to make it fly. There were no forced acronyms and no one felt the need to anthropomorphize their project by giving it a name. Maybe that – ultimately – is the difference between robotics and mechatronics.

Member discussion